From the Philadelphia Business Journal:

Steering the ship: Inside PhilaPort’s plan to better compete with the East Coast’s biggest ports

Philadelphia, Mar 24, 2020 11:11am EDT —

Below towering blue cranes grasping 25-ton shipping containers at the Port of Philadelphia is a claw dipping rhythmically into the Delaware River, pulling up sediment as excess water flows from its grip.

The more than decade-long dredging effort to deepen the river to 45 feet, along with a separate project to create PhilaPort’s first new berth in 50 years, will allow the port to accommodate bigger ships with more cargo.

It’s all part of a plan to grow container capacity by 18%, with the ultimate goal of making PhilaPort more competitive with its peers up and down the East Coast. Since dredging of the Delaware River began, the ports of Baltimore and New York have deepened parts of their channels to 50 feet, while Norfolk is currently conducting a dredging process to 55 feet.

“Where we are today is only a whisper of where we can be 10 years from now,” said Jerry Sweeney, PhilaPort’s chairman since 2015 and CEO of Brandywine Realty Trust.

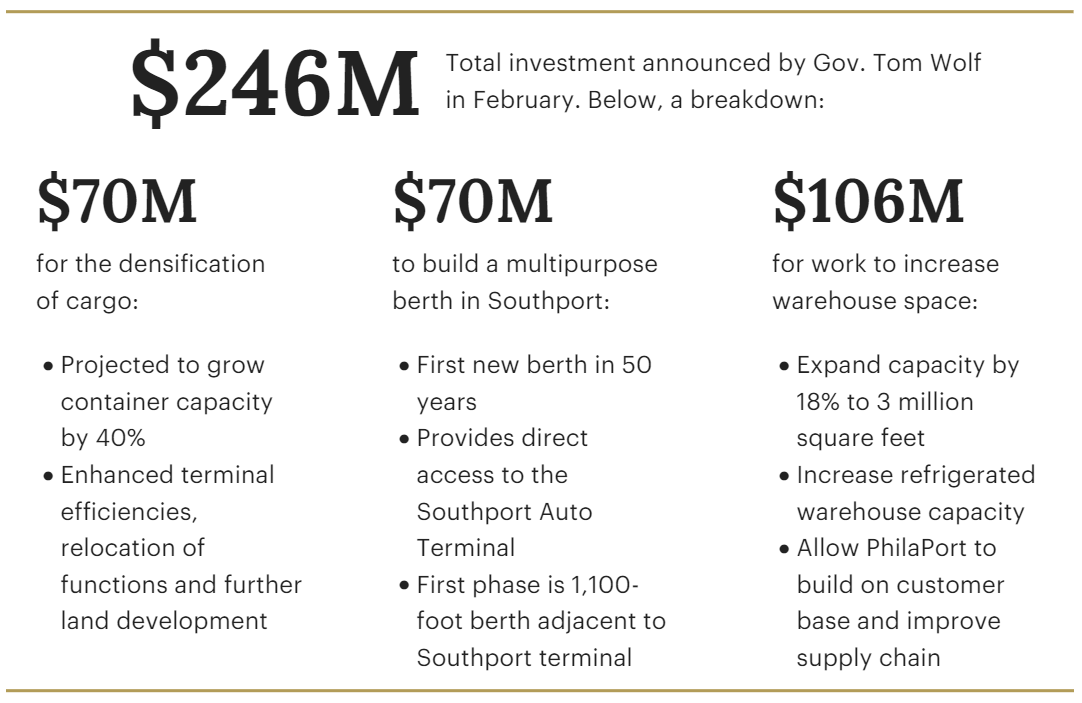

The depth of the Delaware River isn’t the only thing the state-run agency is expanding. The plans for growth are ambitious and building momentum. PhilaPort is coming off a year in which it topped the U.S. average for container transport, led all East Coast ports in refrigerator transport, and received $246 million in additional state funding.

To help accommodate the growth, port leaders want to spend some $176 million on building new warehouses, as well as purchasing and developing new land.

Since Sweeney became chair seven years ago, the port has received over $500 million in state funding, turning a port that was operating at a loss into one with positive cash flow and generating close to $100 million in annual tax revenue. Sweeney and PhilaPort CEO Jeff Theobald, who has been in the role since 2016, charted their course to competitiveness into three phases.

“Our mission was to stabilize the port, [then] get into a growth mode,” Sweeney said. “We’re in that second phase and now the real opportunity is, with this additional investment, to really accelerate that growth curve.”

The port’s 16% increase in containers in 2021 outpaced the 14% average across U.S. ports, and the more than 7 million tons transported last year broke its previous record of 6.9 million set in 2017. The Port of Baltimore, by comparison, transported nearly 11 million tons in 2021, and the total was over 25 million tons at the Port of Virginia in Norfolk.

Amidst the uptick in productivity, Theobald said there was just one case where ships were held back in Philadelphia last year, compared to other ports, particularly on the West Coast, where lengthy ship backlogs caused delays of weeks or months in the supply chain. In Philadelphia, operations were suspended for three days in early September as crews worked around the clock to decongest the docks.

Leo Holt, the president of Holt Logistics, which has managed operations on Philadelphia’s ports for nearly 100 years, said the lack of backlogs and the ability to maintain a relatively normal supply chain was a direct result of previous investments, both public and private.

“[PhilaPort] could not be busier without falling on its face,” Holt said. “We do not have the issues that Los Angeles, New York and Savannah have in terms of ships waiting to unload. But we would have had all those people not made their bets starting with Gov. Wolf. Having said that, we now need to double down to keep up the pace.”

Theobald and Sweeney attribute the port’s increased pace in large part to focusing on a “niche market.” PhilaPort is the East Coast leader for refrigerated cargo, which made up the largest portion of its cargo in 2021 at 36%.

White containers, an indicator of refrigerated cargo, dominate the docks at the Packer Avenue terminal. There, some 80% of incoming cargo is refrigerated fruits, nuts, vegetables and meats — products requiring quick turnarounds to grocery stores and retailers.

The leadership team wants to ensure it has the bandwidth to continue growing not only its refrigeration business, but its overall capacity for general cargo as well.

That means potentially adding a warehouse specifically for refrigerated goods on Packer Avenue next to a new $42 million warehouse expected to be completed in May. The port is looking to add as many as three new warehouses in the coming years in South Philadelphia and at the Tioga Marine Terminal a few miles north. Overall, the projects could cost an estimated $106 million and increase warehouse capacity 18% to 3 million square feet.

Port officials say they have space for the three new warehouses, but finding land for additional growth could be a challenge. In South Philadelphia, the port is hemmed in by the sports complex, the Navy Yard and a residential area. At the Tioga Marine Terminal, the port’s North Delaware Avenue facilities back up to I-95, leaving officials with somewhat limited options for physical expansion.

Theobald said one option is to build out finger piers between Packer Avenue and the Southport Auto Terminal operations, effectively allowing more ships to dock and more cargo to be processed. It would be a longer-term project but would make use of what is now unused land between the two facilities.

Meanwhile, Hilco Redevelopment Partners’ planned redevelopment of the 1,300-acre former Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery site in South Philadelphia is another opportunity for increased space. The HRP project, known as the Bellwether District, is adjacent to Southport, situated near the Delaware River and is expected to house up to 15 million square feet of life sciences, e-commerce and logistics space as it builds out over the next 13-15 years.

Holt said HRP is reserving about 150 acres at the site for beneficial cargo owners — importers of goods who do not use third parties to ship them. Even if the vast space isn’t owned by PhilaPort, it could attract tenants that would bring more ships and more cargo to Philadelphia. The developer worked on a similar project outside of Baltimore which now houses tenants like Amazon, Under Armour and FedEx.

“They have what I’m going to call dream-it-and-we-will-build-it space available for people,” Holt said. “Philadelphia isn’t a place where we over-imagine something, but these are people who have taken fallow ground — ecologically and environmentally challenged ground — and turned them into absolute employment engines. That’s what I see for the Hilco space. It can only spell good things for Philadelphia.”

Theobald said PhilaPort is currently in talks with HRP officials regarding planning at the Bellwether District.

John Vickerman, a port consultant who runs Williamsburg, Virginia-based Vickerman and Associates, believes Philadelphia can compete with ports like New York, Savannah and Baltimore over the next decade. He sees “a growing need” for PhilaPort to distinguish itself in order to compete with its peers to the north and south, and said to do so it will be “almost mandatory” to build an intermodal facility.

Currently, PhilaPort has two separate railroads to transport its auto cargo and container cargo just off the port. An intermodal facility would seamlessly transfer cargo containers from ships to trucks and trains for transport right at the terminal, Vickerman said, effectively increasing the amount of cargo the port could handle with quicker turnaround times.

Theobald feels that the two railroads currently serve as a quasi-intermodal facility but didn’t rule out building one as part of the port’s long-term plans.

Increasing capacity or density will be a pressing need as bigger ships with more cargo begin coming into the port. PhilaPort’s work to provide more deepwater space will allow some of the largest ships coming to the East Coast to dock in Philadelphia.

The 10-year deepening of the Delaware River’s main channel from 40 to 45 feet for a stretch of 120 miles is set to be completed in early 2023. The $480 million dredging is being completed in partnership with the Army Corps of Engineers, with $150 million in funding for the project coming from the state’s first investment.

In South Philadelphia, the port is constructing its first new berth in about 50 years that will complement the Delaware River dredging project. The multipurpose, deepwater berth is still about four years from completion but will give ships direct access to the newly completed Southport.

As that dredging machine continues to dip into the Delaware River to clear the way, Sweeney and Theobald are working to build an economic engine they hope will echo throughout the state.

“Not only is the port delivering today, but it’s really well positioned to deliver tomorrow,” Sweeney said.

##

Philadelphia Business Journal

Mar 24, 2022, 11:11am EDT

Ryan Mulligan, Digital Producer

PhilaPort, The Port of Philadelphia, is an independent agency of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania charged with the management, maintenance, marketing and promotion of publicly-owned port facilities along the Delaware River in Philadelphia, as well as strategic planning throughout the port district. PhilaPort works with its terminal operators to modernize, expand and improve its facilities, and to market those facilities to prospective port users. Port cargoes and the activities they generate are responsible for thousands of direct and indirect jobs in the Philadelphia area and throughout Pennsylvania.

PhilaPort, The Port of Philadelphia, is an independent agency of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania charged with the management, maintenance, marketing and promotion of publicly-owned port facilities along the Delaware River in Philadelphia, as well as strategic planning throughout the port district. PhilaPort works with its terminal operators to modernize, expand and improve its facilities, and to market those facilities to prospective port users. Port cargoes and the activities they generate are responsible for thousands of direct and indirect jobs in the Philadelphia area and throughout Pennsylvania.